Fascism as degenerated centrism

The Centre soul is an ethernal struggle between Orleanists and Bonapartists

When we talk about politics people almost always ask themselves what "right" and "left" mean. Over the decades, a myriad of historians and political scientists have tried to answer this question, and everytime they didn’t find a final answer. That’s because, as Matthew Yglesias wrote a few months ago, though "right" and "left" still define two different kind of societal vision (one aiming to preserve hierarcies and tradion, the other one leveling up social differences), the two dichotomies are sensitive to inevitable societal changes. But besides that is pretty curious almost no one wonders what “center” means. After all, the center is considered the ideal point in wich both right and left should pivot in order to get a sufficent consensus to rule, but you don’t read a lot of analysis about, politically speaking, what kind of philosophy and societal vision a so called “center” aims to deliver.

A potential answer to this question has been provided by the French historian and essayst Fabrice Bouthillon. In his essays: Nazisme et révolution : Histoire théologique du national-socialisme, 1789-1989 and Bonaparte comme précurseur: Rapport sur la banalité du mâle, Bouthillon deline an original and out-of-schemes analysis on the original roots of European fascism and 20th century totalitarianisms in general. According to Bouthillon, history of 19th and 20th cetury should be read as a constant attempt to restitch the political fracture caused by the French revolution. Everybody knows “right” and “left” were born exactly during the French revolution, in wich with “left” was referred anyone wanting replace the ancient regime with a new democratic and egualitarian order, while with “right” were considered those one wanting to preserve the old order in name of hierarcies and tradition. Of course we are not talking about two divergent opinions you can try to converge with a civil debate on Ophra Winfrey show or Joe Rogan podcast, they were two clear irreconiliable views wich inevitably degenerated into civil war. And it was exactly in this irreconciliable chaos between right and left that the “center” emerged. Before to go more into the topic, we must before make a digression on French political history. Historically, conventional wisdom retain the French right was divided into three wings:

The Legitimists, according to the only and legit entity to rule France was the king alone, and every entity opposed to the monarchy has therefore no right to exist;

The Orléanists, a political movement emerged during Louis Philippe I of Orléans, in favor of a liberal constitutional monarchy;

The Bonapartists, directly inspired by Napoleon.

Now, according to Bouthillon the conventional divide among the French right is actually misleading. In his opinion, only legitimists should be considered the authentic right, while the latter two tendencies should be included to the Center. It is with Legitimists, indeed, that the irreconcilable divide between the idealist and egualitarian left represented by Jacobins emerged. And between these two tendencies both Orleanism and Bonapartism, rather than two right wing factions, are actually two opposite kind of centrism. In this context, Bouthillon define Orléanism as a “centrism by exclusion of extremes”, a moderate tendency aimed to reject both the most assertive tendencies of progressivism and conservatism. On the other hand, Bonapartism is conceived as “a centrism through addition of extremes”. Logically, that’s make it both further to the left and more to the right than Orleanism.

Getting back to the French Revolution, while the Directory could be considered as a failed proto-Orléanist attempt, Bonaparte charged himself to put an end to the civil war opened by the Revolution between the left and the right, installing an authoritarian regime with both monarchist and Jacobin elements.

It is therefore this political option, the centrism through addition of extremes, that Fabrice Bouthillon relates to the dictatorial regimes of 20th century:

“the wave of totalitarianism between the wars was a second version of what the two Bonapartisms had been in their time, and this, because both faced the same political challenge: finding a solution to the revolutionary separation of the Left and the Right, after the failure in the matter of centrism by exclusion of extremes”.

Regimes evolution and their relationship to war (the parallels between the 1st Empire and the 3rd Reich are particularly striking, and not only with regard to the Russian campaign), as well as relationship between fascism and the Church, the reference to the old Roman imperial idea, but also the concrete filiation of a policy of overcoming the left and the right via the Second Empire and French Boulangism, provide a solid argument for the theory of a genealogy of authoritarian Caesarism, of which Bonaparte forms the historical precedent.

If we extend Bouthillon's analysis to post-WWI Italy and Germany we will notice as well, how both countries found themselves in a situation not very different from post-revolutionary France.

In fact, after the war, the two countries found themselves deeply divided into two opposite factions: the socialist internationalists on one side and the national bourgeoise on the other side. In Italy it was Mussolini himself with invention of fascism, whose basic doctrine aimed to pacify society by combining national greatness with social policies, who like Napoleon 100 years before, installed an authoritarian regime to put an end to the quasi civil war wich was leading Italy on a cliff. In Germany, following Mussolini’s example, Hitler invented national-socialism, wich like fascism aimed to overcome divisions among German society installing a totalitarian regime with both right wing and left wing elements.

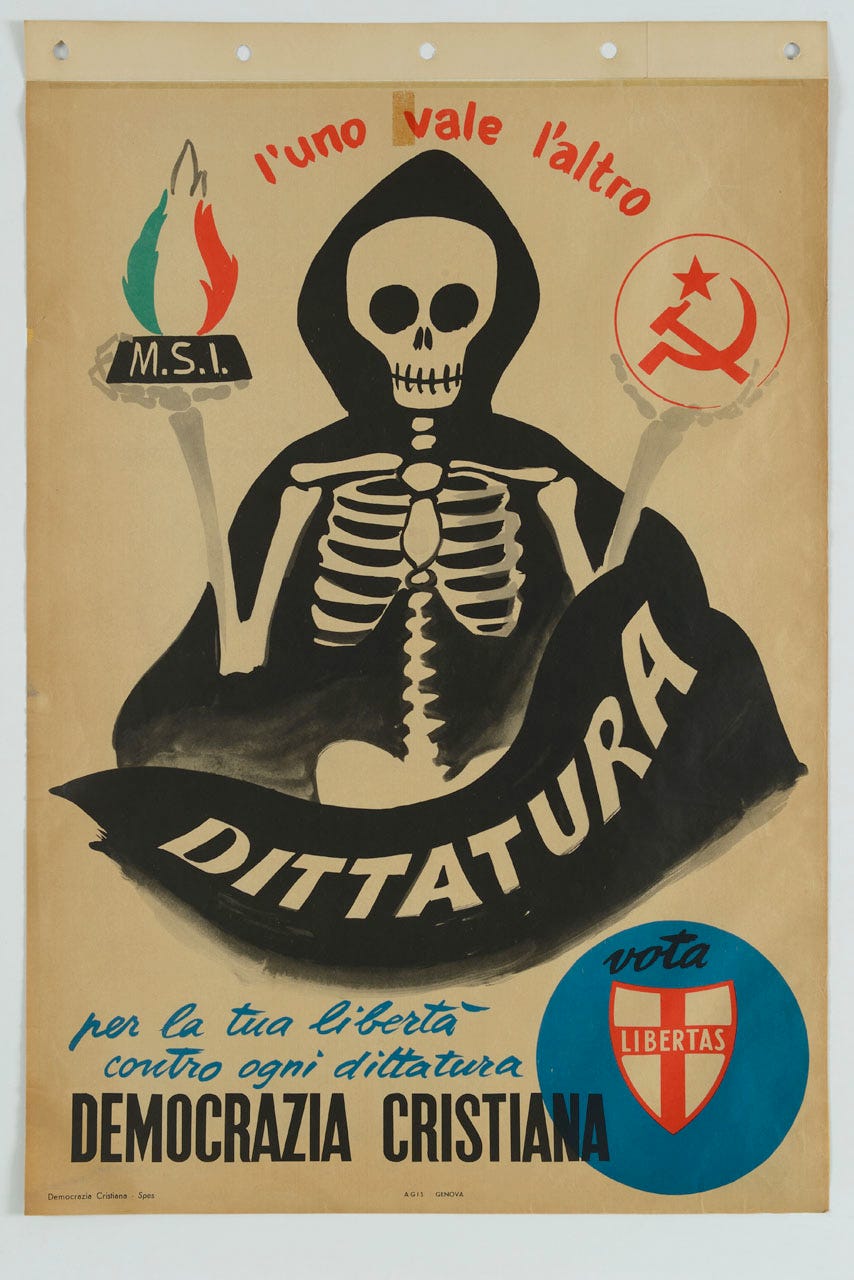

Furthermore, it is quite instructive to notice how after the fall of the two regimes, both in Italy and in Germany an Orleanist logic imposed itself. In fact, after the war, for fifty years both Italy and Germany got ruled by two big Christian Democratic parties, sometimes ruling alone, quite often forming coalitions aimed to keep out the extremes (if before the war the extremes were the communists on the left and the conservative nationalists on the right, now they were the communist on the left and the neo-fascist/neo-nazi on the other side).

One could argue the long wave of French Revolution has never stopped to producing its effects.

For a long time political analysts had enormous problems to codify fascism and nazism. If you ask to a leftist analyst about fascism, he would declare both the regimes in Italy and Germany were reactionary dictatorship financed by Big Business in order to prevent a marxist revolution in Western Europe. If you ask to a libertarian, he would declare actually fascism and nazism were socialist regimes because of the “S” word on “National-Socialism” and because Mussolini was a member of the Italian Socialist Party in his youth. But if we accept Bouthillon paradigm we can conclude either the leftist and libertarians are both right and wrong at the same time. When in fact they talk about fascism, they happens to be unable to grasp Its true nature because they conveniently consider only those elements wich match with their prejudice, while negleting all others.

Obviously, there are also elements that can be criticized in Bouthillon's theory. What seems more problematic is the general framework within the author wished to place his thesis. A significant fragility, which leads him more than once to resort to harmful generalizations, for example when he extends the "stuttering repetitiveness of the totalitarian phenomenon" from the Pharaohs of Egypt to Hitler, via Caesar, Napoleon or even Stalin. An association which, precisely, poses a problem in several respects, especially if we take seriously the thesis of centrism through addition of the extremes. It’s indeed a bit pernicious to consider Stalinism either on a programmatic or even historical level a fusion between the right and the left. On the contrary, Stalin's regime can be absolutely cosidered as a product of the total triumph of one extreme against another. The dictatorial and national form of Stalinist communism, the endogenous reasons for the ideology aside, seems in fact to be much more the result of necessities presented by the repressive maintenance of ideological monopoly than a doctrinal choice consisting of adding to it a right-wing dimension, in the hope of overcoming a divide which, due to the very policies of purification, no longer existed. It is of course quite different for Italian fascism and national socialism, which carry in their doctrine, just as in the condition of coming to power, the desire to make the internal divisions of the nation inoperative by the union of opposite tendencies.

However, besides these kind of legit reservations, there is very little to say about Bouthillon’s thesis. A thesis capable of complementing, and perhaps rebalancing, those made by prominent historians like Ernst Nolte or Zev Sternell, who based most of their analysis on fascism tracing their roots on Charles Maurras or George Sorel. But refocusing this lineage on Bonapartist tradition, the author has been able to give a convincing conceptualization to long standing ambigous terminologies like “fascism” and “centrism”.

I think this was only true when left of center meant communist.

But I have asked myself too why is it so that if every ideology has moderate and radical versions, why do Nazism and Fascism only have radical versions? And what I found it does have a moderate version, a kind of combo of left-populism and right-populism represented by Orbán and perhaps Five Stars.